by John F. Di Leo

Reflections on Constitution Day

September 17, 2018 A.D.

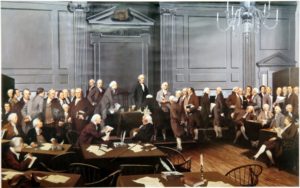

On September 17, 1787, thirty-nine of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention got together for one final time, to sign the final document before sending it out to the states for ratification. (pictured: the Signing of the Constitution, by Louis S. Glanzman)

There were 55 delegates in all, that momentous summer in Philadelphia, though all were rarely present at the same time.

They had spent the summer debating both the big picture – what was to be the relationship between the federal government, the state governments, and the people? – and the small picture – exactly what roles should each branch have, when all is said and done? It was a summer of debate and argument, of philosophy and practicality. And it all occurred behind closed doors, in a hot and humid summer more than a century before air conditioning.

It had been a long road to this point, with each state selecting their delegates in the spring, some intending to help and others doing their best to thwart it. Some of the nation’s greatest patriots – Governor George Clinton of New York for example, and Governor Patrick Henry of Virginia too – actually did everything they could to stymie the effort, as the old way seemed better-suited for their own interests.

But even that long summer and the springtime of negotiations and delegate selection that preceded it don’t tell the whole story. The story of the United States Constitution goes back far indeed.

These United States started out as individual colonies, each one chartered separately by England (or won away from other countries by treaty). Formed by different types of settlers for different types of settlement, they had little in common at their respective foundings, and still had little in common in the mid-1700s.

But in the 1760s, all of a sudden, these colonies began to note some important common ground between them: the government of England under the Hanoverian kings, particularly this young new king, George III, was treating them like second class citizens.

English citizenship was a mark of pride. Far different from citizenship in many other monarchies, where one was just a subject, to be ordered around by one’s monarch or his nobles at their whims, English citizenship carried with it 500 years of precious common law, not to mention 500 years of hard-won freedoms.

From 1215’s Magna Carta to 1628’s Petition of Right and beyond, an English citizen was guaranteed true rights, such as representation in the House of Commons, jury trials, and protection from unlawful seizure of property. The government could not tax a person, for example, unless his representatives in parliament had approved such a tax.

King George III, however, had no interest in applying such protections to the American colonists. To him, those of us across the Pond were mere subjects; he disregarded the precedents of such of his predecessors as King James I, who had guaranteed these rights to American colonists in writing, over a century before.

When George III saw the expenses arising from the Seven Years War, he decided to have the Americans share in their costs – but not by appealing to their respective legislatures for a legal approach. He simply directed his pawns in Parliament – which had no American legislative representation at all – to pass funding schemes on their own, bypassing the people’s elected representatives, in direct contravention of centuries of British law and of the colonies’ royal charters.

American colonies began to band together in the 1760s. Colonies chipped in to send Benjamin Franklin to England as their lobbyist. Activists rose up against the Stamp Act, holding a Stamp Act Congress, the first true collaboration between American colonies. Then came more as the 1760s marched on – the Intolerable Acts, the Townshend Acts – so many distinct attacks on American colonists, all seen by proud Englishmen (as we still were, back then) as utterly illegal. Leaders such as Samuel Adams and George Washington organized a coastwise boycott of English trade in protest.

So when the American colonies called a First Continental Congress, and then a Second Continental Congress, the march to unity that George III had unintentionally set in motion became irresistible. These colonies were now aligned, by both common heritage and the recognition of common abuses.

And so we went to war – a long one, eight and a half years from the first shots at Lexington and Concord to the signing of the Treaty of Paris.

But this war needed some structure to enable collaboration, however loose, between these many states, so the Continental Congress concocted Articles of Confederation, a set of agreements that would enable the colonies – now calling themselves states – to share a common response. Under these loose Articles, the states could cooperate in war, share in the Continental Army and Continental Navy, negotiate as a block with foreign nations. But these articles did not, by any stretch of the imagination, make the United States of America a single nation in itself.

The Articles of Confederation were proposed in 1777, relatively early in the war… ratified by the states in 1781, as the war approached its end… and were clearly severely lacking even before they were ratified. The national “government” under the Articles had no power to raise money domestically; it had no ability to force states to contribute or pay troops, and every state delegation had a veto on every measure, so nothing of substance could ever get done.

The final years of the war were marked by such unanimous recognition that the Articles were weak that delegates to the Confederation Congress often didn’t bother to attend the sessions. As early as the year the Articles were ratified, such congressmen as Alexander Hamilton were proposing options for their improvement or replacement.

In 1786, the war over and the nation still in economic depression, some states called for a meeting. Known as the Annapolis Convention, this poorly-attended gathering was used to launch a more serious project: a true constitutional convention the following year. So it was that the failed meeting at Annapolis served as the lynchpin that set the successful meeting at Philadelphia in motion.

And what was the Constitutional Convention of 1787 about?

It was arguably a gathering of the most dedicated patriots in one place ever assembled. Carefully chosen by their state legislatures and governors, these were thoughtful people with years of service to the philosophy of freedom.

Virginia sent George Washington, who had spent 20 years as a legislator before taking command in the War of Independence, arguably the first true advocate of thinking of the colonies together as a nation, rather than as separate little countries. And Virginia sent James Madison, a historian and philosopher who had made the history of republics a specific area of study. Virginia also sent George Mason, neighbor and political mentor of Washington, best known for his devoted advocacy of Bills of Rights.

Delaware sent John Dickinson, author of the Olive Branch Petition that preceded the Declaration of Independence. And Delaware sent George Read too, a longtime state legislator who had signed the Declaration of Independence when fellow delegate Dickinson declined back in 1776.

Pennsylvania sent financier Robert Morris, who had kept the army going throughout the war despite a constant state of insolvency. And Pennsylvania sent Benjamin Franklin, most famous of the nation’s elder statesmen, whose imprimatur gave the event unquestioned weight. Pennsylvania even managed to send New Yorker Gouverneur Morris, who couldn’t represent New York because he was living in Pennsylvania for business at the time, so Pennsylvania proudly snapped him up as a member of their own delegation.

Even New York’s delegation was impressive, despite its governor’s best efforts to foil the process. Governor Clinton had to send Alexander Hamilton, a pro-reform delegate, but for his anti-reform majority, Clinton sent patriots Robert Yates and John Lansing, whose opposition was sure to come from unquestionably honorable hearts.

All in all, there were 55 delegates that summer, virtually all of whom had been state and federal legislators for years. 25 of them had served in the Continental Congress and 40 had served in the Confederation Congress, so they knew the flaws of the existing system from painful personal experience. 8 delegates had been signers of the Declaration of Independence, and 15 of them had worked on the committees that drafted their respective states’ constitutions back when independence was declared.

Living in the modern era, we have become accustomed to politicians winning elections without government experience. Businessmen, sports stars, comedians, and people who just inherited their wealth have spent their millions to secure seats in the House of Representatives, the Senate, and even Governors’ mansions without ever having had to truly evaluate the philosophical questions of republican governance.

By contrast, the state governments of 1787 understood the challenges that this convention would face, so, for the most part, they sent their best – their most thoughtful, their most experienced, their most practical – in hopes that they could find a path to solve the problems that government under the Articles of Confederation had faced, without surrendering the very rights that they had fought a revolution to protect.

So these delegates spent that summer finding balances… picking and choosing elements of state governments and other governments from history that worked, using the English system they knew best as a part of their foundation, but removing its key flaws and redistributing government’s appropriate powers across the branches, in the “checks and balances system” of shared sovereignty that we cherish today.

For example, they brilliantly recast the concept of a House of Lords as a Senate that would represent the state governments, giving that body the power to approve or reject executive appointments, federal judges, and treaties with foreign powers.

This wasn’t done in a day… but this compromise in setting up the House and Senate – balancing the importance of responsiveness to current public opinion (in the popular election of the House) with the importance of tethering the federal government to the stability and sovereignty of the state governments (in the state selection of Senators) – was one of the greatest achievements of political science in human history, and could only have been accomplished by this particular group of thoughtful, experienced delegates.

It is inconceivable that a modern convention – of people elected in the way we choose representatives today – could come up with such a plan.

By the end of August, 1787, three months of notes, three months of debates, three months of competing visions, had been narrowed down to dozens and dozens of clauses scribbled in 23 bundles of parchment… which the convention handed to Gouverneur Morris for the job of organizing it, so that it would be available for final approval and signatures on that long-ago September 17.

In some ways, the Constitution is the accomplishment of the people who fought for the convention itself to be held – primarily Washington, Hamilton, and Madison.

In some ways, it can be attributed to those delegates who participated the most in the floor debates, producing the many distinct compromises that filled those bundles of notes – primarily James Wilson, Gouverneur Morris, Roger Sherman, James Madison and George Mason.

And a case can also be made that the single person most responsible for the Constitution’s success is Gouverneur Morris, a delegate almost by accident. It was Gouverneur Morris of upstate New York, serving as a delegate for Pennsylvania, who organized those stacks of notes into the coherent, rational masterpiece we know today.

Contrary to popular opinion today, the Constitution is much more than just a blueprint for elections.

In school, we are shown how the Constitution lays out our elective options: we vote every two years for congressmen, who must be at least 25. We vote every six years for Senators, who must be at least 30. We vote every four years for a President and Vice President, both of whom must be at least 35, be natural born citizens, and be from different states in order to win their numbers in the Electoral College.

But that’s not really what matters most about the Constitution. What the schools don’t teach anymore – either because they want to suppress the knowledge, or because they never learned it themselves – is that the Constitution is itself a border wall around the federal government, designed to keep the nation’s capital from exceeding its proper authority.

These two, four, and six year terms are just tools among many, not an end in themselves. The true goal of the Constitution wasn’t to divide powers, it was to cap them. The Constitution – primarily through the US Senate – is designed to keep the city of Washington DC from infringing on the proper rights and powers of the states, the counties, the townships, the cities, and individual American citizens.

There have certainly been errors in the years since. By the end of the 19thcentury, there were states that fumbled their duty in appointing senators, paving the way for the fatal error of the 17th Amendment. And ever since that day, the walls erected by the Constitution have been crumbling, with the federal government expanding in all directions, in direct contrast to the plans of the Framers.

But the mistakes of this past century don’t diminish the incredible accomplishments of the Convention that produced over a century of unprecedented success.

The America of the 19th century – when the federal government was truly limited as the Founding Fathers intended – enjoyed massive economic and cultural growth, a kind of growth that can only occur when the jack boot of government is kept off the neck of the citizenry.

That period of greatness – before the 17th Amendment crippled the plan – lasted 120 years, a truly amazing accomplishment by any standard, and one which fully deserves our celebration today… not just every September 17th, but every week, every day, every hour in which we enjoy the privilege of drawing breath as citizens of this miraculous country, the greatest nation on God’s green earth.

Copyright 2018 John F. Di Leo

John F. Di Leo is a Chicagoland-based trade compliance trainer, writer and actor. A former chairman of the Ethnic American Council in the mid-1980s and the Milwaukee County Republican Party in the mid-1990s, his columns are regularly found in Illinois Review.